Civic Community

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station Unites Wood, Forest, and Landscape

Perched on a ridgeline in Maine’s Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, the nearly all-wood Tekαkαpimək Contact Station seems to float among the trees yet anchors firmly to granite bedrock. Conceived under the mandate to “use wood, use local,” the park and cultural center employs CLT floor slabs, custom-fabricated glulam columns and beams, white cedar cladding, and Douglas fir interiors. Designed with the Wabanaki Advisory Board—an alliance of Indigenous Maine tribes—the structure feels like a sanctuary, framing views to Mount Katahdin outside while embedding Indigenous stories and artwork within.

Building on Maine’s

Timber Legacy: Rooted in Wood and Place

“From the very beginning, the conversation for the contact station was about how to make wood central—not just as a building material, but as a way to honor both Maine’s timber history and its Indigenous traditions,” says Edward Parker, partner at Alisberg Parker Architects, the architect-of-record for the project. Todd Saunders—a Canadian-born architect who has lived and worked in Bergen, Norway, for more than three decades—designed the contact station in close collaboration with Parker’s firm.

“The owner’s vision was clear—they wanted wood to be the structure, not just a finish,” adds Chris Simmons, project executive for Wright-Ryan, the general contractor for the project. “That meant figuring out how to source components locally wherever possible and addressing how each system and connection could be built on a remote site.”

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station was funded and developed by the Elliotsville Foundation, which is led by Roxanne Quimby (co-founder of Burt’s Bees) and her son Lucas St. Clair. A philanthropic organization focused on conservation and sustainable economic development, it donated 87,000 acres to establish the facility. Unlike a visitor center, a contact station is generally a smaller facility that orients visitors to nearby topography, trails, and waterways. At Tekαkαpimək, Quimby’s vision extends beyond that—making it a cultural space that shares local Native American stories, culture, and art through the architecture itself.

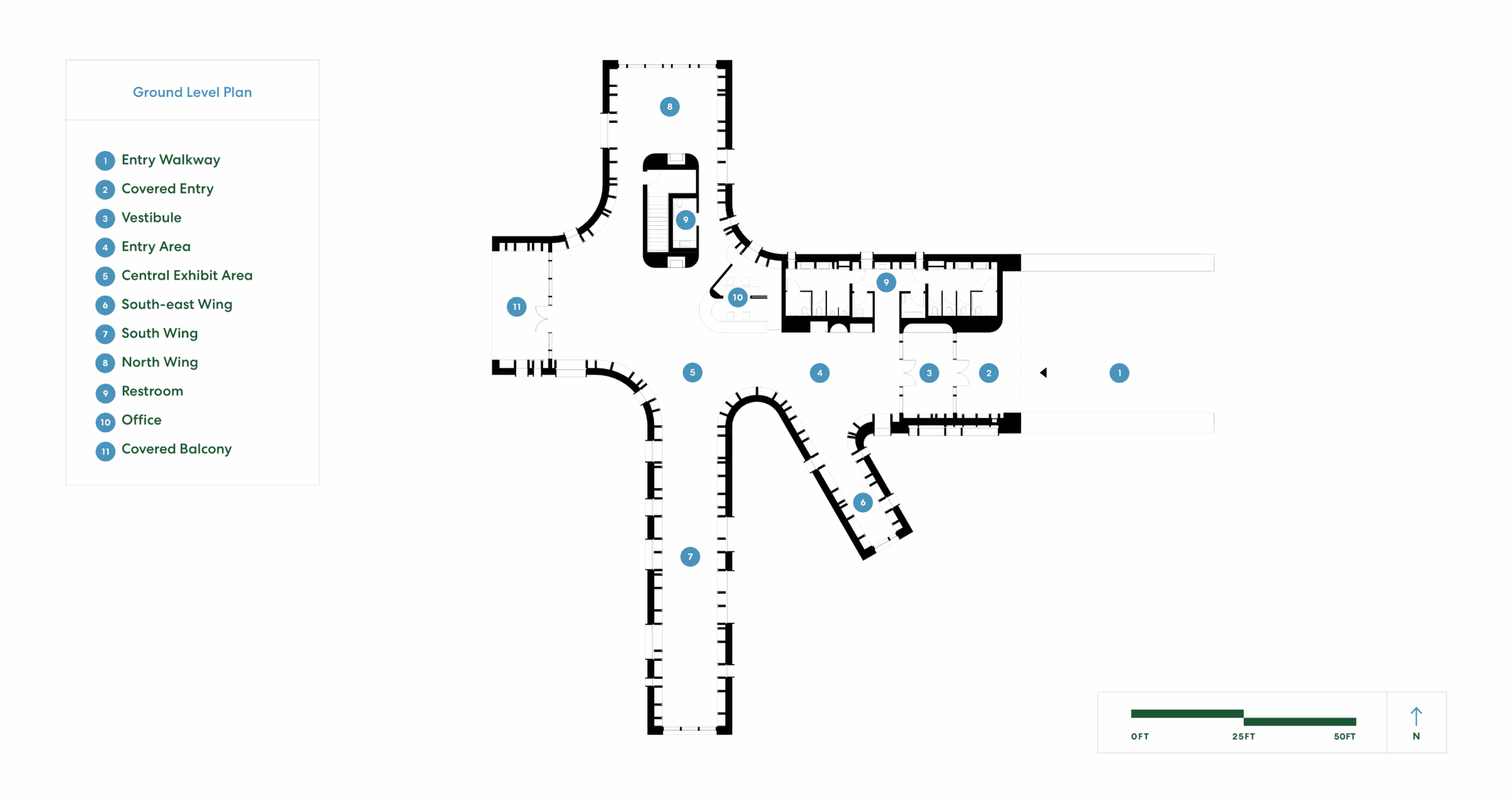

The station is organized as a series of intersecting wings, each projecting into the forest canopy and curving softly toward the central point where they join. The nearly 8,000-square-foot building includes reception, orientation and services, exhibition spaces, and gathering areas—including a large hall with three fireplaces, seating, and an outdoor balcony with panoramic views of Mount Katahdin. The grounds also include an outdoor gathering circle with a Wabanaki double curve motif constructed from locally quarried granite.

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

Visitors enter the cedar-clad center from the east; inside, they are enveloped by the double-height, light-filled interiors, as well as by the biophilic benefits of warmth and the scent of exposed wood. The curvaceous ceiling—clad in Douglas fir tongue-and-groove boards—doubles as wayfinding, drawing visitors through Indigenous exhibits as they proceed to sweeping west-facing views. South-facing windows, equipped with shades that reduce solar gain, help warm the interiors with passive heat, while the north-facing windows offer expansive views of the sky. From the building’s centerpoint, visitors can take in views from all directions.

The building is designed to operate independently of the electric grid, relying on passive strategies for comfort. “The building works like a thermal battery,” Parker explains, noting that it runs primarily on solar arrays. Instead of air conditioning, temperature is managed through radiant floor systems and natural ventilation through operable windows and vents that create convection to keep air moving. A generator offers backup power, but the intent is for the building to operate fully on solar power generated on site.

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

The design team’s work on the project included consultation with the U.S. National Park Service and the Wabanaki Advisory Board, which was integrally involved to ensure Indigenous culture and perspectives were fully realized in the final design.

But the final design represents a solution that was shaped as much by the challenging site as by the mandate to reflect Wabanaki culture and reduce its carbon footprint. “One of the things we wanted to do was really have this light touch to the site and environment,” Parker says. “The idea was that it would feel nestled in the forest—like a treehouse—while anchored to the mountain.” With only a thin layer of soil over a solid ledge, the building is essentially pinned directly to bedrock, reducing the need for heavy foundations. Glulam beams, columns, and CLT decks keep the structure comparatively lightweight, while still allowing for dramatic cantilevers. Beyond light-frame and mass timber construction, the nearly all-wood structure uses just two steel I-beams.

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

Simplicity Meets Complexity: Forest as Setting, Forest as Structure

Getting to the site takes visitors on a half-hour journey off I-95 on roads that wind through small towns and dense forest. From the parking area, the approach continues on foot, climbing toward the ridgeline. There, the Tekαkαpimək Contact Station emerges gradually as the dense forest gives way to a thicket of young yellow birches.

“So you can imagine accessing the site was not easy. For the mass timber, we used large prefabricated pieces, like CLT, that arrived on flatbeds and were craned into place in just two weeks,” Parker explains. That speed was critical since the site is inaccessible from November through April. Simmons adds: “We literally had to build a road just to reach the site—about three miles in total.”

The building’s overall structural design takes its cues from the forest itself. Columns are set at varied intervals, four types in all, creating a deliberate irregularity that breaks from conventional symmetry. “When you’re inside, it feels like being among trees, with the art and light woven through. It’s an experience of being both in a building and in a woodland clearing at the same time,” Parker says.

To achieve this look, the columns were anything but typical glulam: Instead of the standard 1×6 laminations, the team used 2x12s stacked on the long dimension. Wright-Ryan, the contractor, fabricated more than 160 of these columns, up to 26 feet tall, entirely by hand in an old potato barn nearby.

“We’d never built glulams ourselves before, but no manufacturer could fit us into their production schedule,” Simmons says. “So we sourced the lumber, set up a makeshift shop, and worked with UMaine to test and certify them. It was a risk, but the only way to achieve the design intent.”

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

The team worked with the University of Maine’s wood testing facility and Alisberg Parker’s engineers to confirm their performance. It was a remarkable feat of tenacity and engineering to get them built—simple in concept, but requiring a highly skilled team of builders, Parker says. The result is a design that offers built-in seating, deep wooden window frames, and integrated alcoves for exhibition display.

The mass timber structure is complemented by light-frame wood construction components. “The simplicity of the materials was intentional,” Parker says. “The glulam columns are built up from stacked 2x12s, and everything is bolted together. It’s a very straightforward kit of parts, the kind of language you’d find in light-frame construction, elevated here through attention to detail.” The roof is also constructed of light-frame elements—all wood trusses, locally made from Maine white pine and reinforced, in some cases, with plywood—and sheathed with structural insulated wood panels (SIPs).

“We used mass timber where the spans and strength demanded it, and light-frame where local mills and crews could contribute,” Simmons says. “That mix gave us both efficiency and a deeper tie to Maine’s forest products.”

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

Despite this complexity of design, there is a certain humility to the materiality and wood products used in the project. “The material palettes in my projects are simple. I grew up with salt, pepper, and dill as spices—that’s it,” Todd Saunders stated in an interview with Architectural Record. “From the outset Todd’s vision was that this could be a building made of nominal lumber and fasteners—beyond the mass timber, many of the lumber and wood products in the building, you could theoretically buy at Home Depot,” Parker points out. It’s this mix of simple materials, intricate design detailing, and careful craftsmanship that really make the building shine and meet the goals it set out to achieve, he adds. “It’s a meticulous execution that speaks of the land, the culture, and the forest all at once,” Parker says.

The contact station “reimagines our relationship with our natural and cultural landscapes,” Saunders writes, “building in balance with challenging terrain, designing with Indigenous sensibilities, and mustering a local workforce in harsh conditions to solve for structural integrity and beauty.”

All Wabanaki Cultural Knowledge and Intellectual Property shared within this project is owned by the Wabanaki Nations.

Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

Project Details

- Project Name:

- Tekαkαpimək Contact Station

- Location:

- Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, ME

- Design Architect:

- Architect of Record:

- General Contractor:

- Size:

- 7,895 square feet

- Wood Products: