Education

Grafton Architects’ Anthony Timberlands Center Is a Story Book of Timber

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

The new Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation is the latest mass timber campus building at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, but it’s no follow-up act. Part of the new Art and Design District located about a mile southeast of campus, the center was designed by Dublin, Ireland-based Grafton Architects, the firm led by 2020 Pritzker Prize laureates Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara. It’s the practice’s first completed structure in the United States as well as its first built mass timber project.

The ATC houses studios, lecture halls, classrooms, and a 12,000-square-foot fabrication workshop for the university’s Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design. “In the eyes of the university, this was not just a building,” the architecture school’s Dean Peter MacKeith says. “It combines teaching and learning spaces with what is, in essence, a research laboratory.”

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

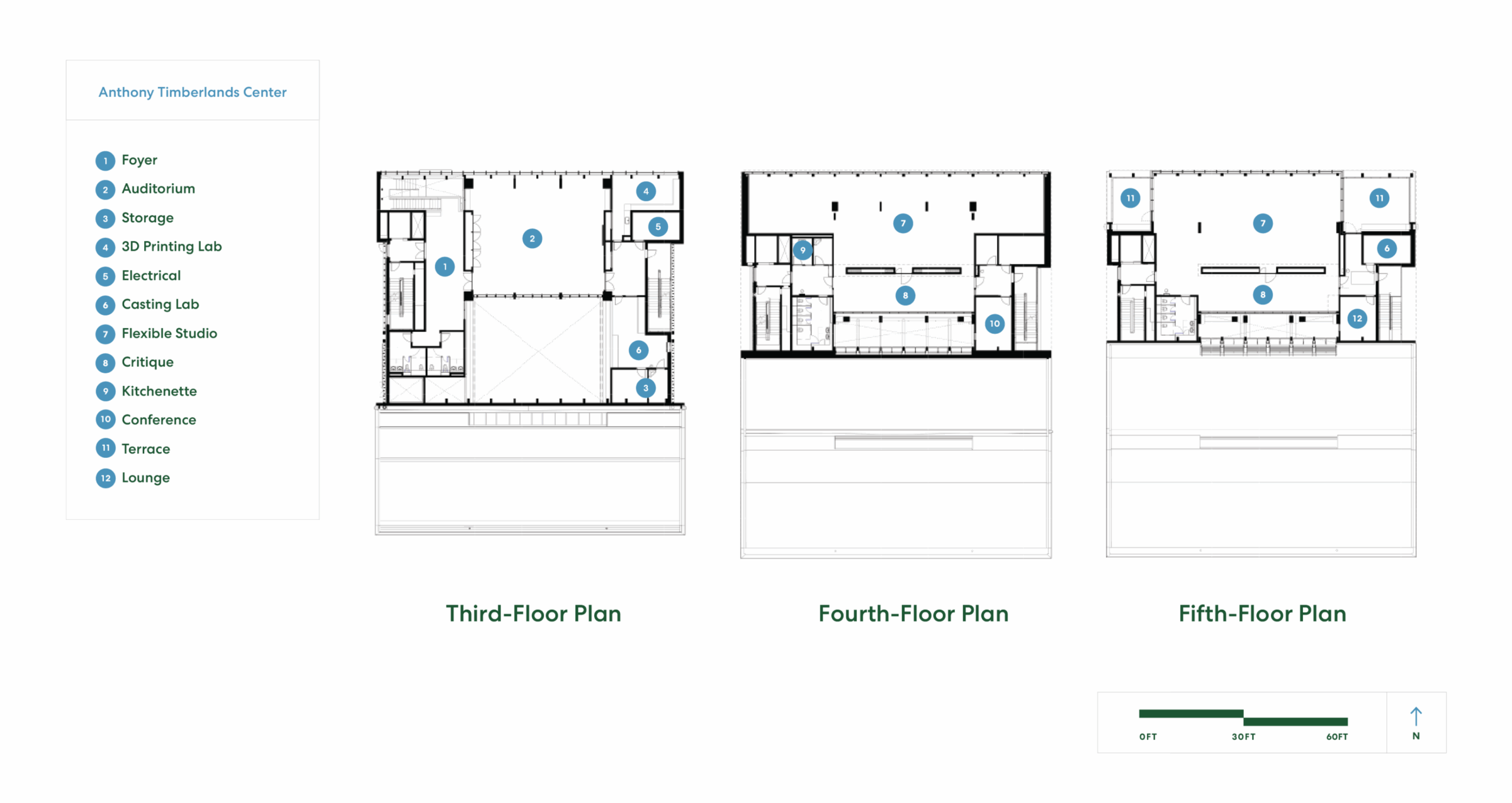

The front of the 42,000-square-foot building rises four stories and faces north onto Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, and places the building’s structure on display. Floor-to-ceiling glazing paired with cutout terraces at the east and west ends reveal the mass timber to passersby. The roof cascades downward toward the back of the building to create a highly memorable profile that reflects the structure’s dramatic interior section. Within, the fabrication lab occupies the 50-foot-wide central bay from front to rear. A 125-seat auditorium occupies the second floor, with open studio and critique spaces on the third and fourth floors overlooking the fabrication lab.

“The university has been this greenhouse for mass timber construction since about 2016-17,” MacKeith says, noting that previously completed projects include the Library Annex by Perry Dean Rogers and the Adohi Hall residences by Leers Weinzapfel Associates. But the addition of ATC adds to this momentum with an additional charge: “The building is intended to be as reflective of the Arkansas forest economy as possible,” MacKeith says. The design team was able to source half of the project’s CLT panels—made of southern yellow pine—from Mercer Mass Timber’s Arkansas factory just hours away. The glulam structural columns and beams were supplied by Austria-based Binderholz.

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

A Display of Material Strength

Grafton Architects was chosen to design the building from among six finalists in an international competition funded in part by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities. The initial RFP drew 69 entries from around the globe. “It was structured to be an educational process as well as an educational outcome,” MacKeith says.

Following the competition, Grafton Architects Project Director Matt McCullagh and Fayetteville-based Modus Studio Partner Jason Wright worked closely together throughout the project. “We were really interested in Thorncrown Chapel [designed by architecture school namesake E. Fay Jones] and that idea about making large scale spaces out of smaller pieces,” McCullagh says. But Modus saw problems with a building based on a lot of delicate pieces and the many connections that would have been necessary. “Maybe we need to pare back the number of components, look at some beefier cross-sectional beams [and] columns,” Wright recalls of those conversations.

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

A distinctive characteristic of Grafton’s designs are spatially complex building sections, and the ATC is no different. The Modus team embraced this approach and dubbed it “the Ozark cross section” as it echoes the Ozark plateau—where the building is located—and its eroded “hollers,” as the locals call its small valleys. “We were able to rally around that section,” Wright says. Seven distinct slopes create what the architects call a “cascading roof” that produces both widely varying ceiling heights within the structure and a strikingly distinctive profile for the building.

Massive exposed glulam columns line the workshop and support the roof and spaces above. “We thought about them as large oak trees lining either side of the fabrication hall,” McCullagh says. “They’re 4 feet by 4 feet at their base.”

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

Wood’s Story Is in the Details

While the program brief called for wood, Grafton partner Yvonne Farrell embraced the metaphoric potential of the material and refers to their solution as a “story book of timber.” On the exterior, a yellow pine rain screen on the lower-level sections contrasts with fire-treated western red cedar at the higher levels of the structure. “Everywhere you go in the building, you see these instances of different materials or different species of timber and there’s a story behind it,” McCullagh says. Those stories will be shared with students who will use the building as a teaching tool for mass timber design and construction.

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

And McCullagh extols the virtues of mass timber on the construction site as well. “If you make [a building] in mass timber, it’s going to be—not quite silent, a quieter construction site and that has a cost benefit that you’re not going to have complaints,” he says.

“There was this idea about the building having a pedagogy of its own for students so that there’ll be these learning moments,” McCullagh says. “There’s a different material and why is that different and what are the properties that are being leveraged here?”

And the team at Arkansas hopes that the Anthony Timberlands Center can be an inspiration to the broader community, as well: “[The building] demonstrates that mass timber can enable expressive architecture as much as it can enable modular housing or speculative office building[s],” MacKeith says. “We call this an exercise in engineering innovation and architectural design innovation as much as educational innovation.”

Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

Project Details

- Project Name:

- Anthony Timberlands Center for Design and Materials Innovation

- Location:

- Fayetteville, AR

- Architect:

- Architect of Record:

- Client:

- University of Arkansas

- Structural Engineer:

- General Contractor:

- Glulam:

- CLT Panels:

- Size:

- 42,000 square feet

- Timber Products: