Multifamily

Montana Workforce Housing Makes Mass Timber Modular

Bucks T-4 Housing

When architect Peter Rose first visited a modular school in Germany built with cross-laminated timber, he ran his hand along a stair joint where two modules met. “With my eyes closed, I couldn’t feel the seam,” he recalled. That moment, he says, changed everything. It upended his expectations of modular construction—not as merely a cost-cutting benefit, but as a precision-crafted system capable of beauty, performance, and permanence.

Now, as a founding partner of Integrated Design Cubed (IDCUBED), Rose and his team are bringing that same European approach to North America. With the completion of the first large-scale mass timber modular building in the United States—a 120-module workforce housing project in Montana named Bucks T-4 Housing—his team is proving that modular housing can be elegant, efficient, and refined.

Bucks T-4 Housing

Bucks T-4 Housing

Bucks T-4 Housing

Cost Savings by Integrating Design and Construction

Modular housing in North America doesn’t have the best reputation. It’s often equated with cookie-cutter, banal, and uninspired design, characterized by bulky proportions, visible seams, and cheap-looking materials, Rose points out.

Modular construction is a form of prefabrication where complete three-dimensional units—built off-site with structure, systems, and finishes—are delivered to the site as ready-to-stack building blocks.

“I have heard some colleagues who ask: ‘Modular—that’s the end of design, isn’t it?’” Rose says. “There’s a huge perception problem and for good reason. A lot of modular just isn’t very good—and people know it.”

But with IDCUBED’s multidisciplinary mass timber approach, Rose and his team are setting out to change that.

“The problem with building these days is that architects are hired by developers, then builders are hired, then subs are hired,” Rose says. “They don’t necessarily know each other or work well together. There is no motivation for them to coordinate at a high level and construction, as a consequence, is a bit chaotic. So we’re very much about the integration of the team.”

It’s a model that includes a partnership between the U.S. architectural firm Peter Rose + Partners and Germany-based NKBAK, as well as collaborations with local suppliers. In this specific project, which included builder Highline Partners and mass timber supplier and module assembler Kalesnikoff. As a turn-key solution, the team offers full design services (building, modules, process of assembly), supply-chain management, module fabrication, and site assembly.

They’re building on the experience of their German partners, NKBAK and Kaufmann Bausysteme, who have completed more than 20 modular mass timber schools and housing projects in Europe, and bringing that expertise to the U.S.

“To achieve cost savings and really make it work, we use digital twins—we design very specifically where each conduit goes, where each pipe goes,” Rose says. “So the design team and the contractors are all designing together and it’s all getting documented very precisely before anything gets built. That’s part of what makes it efficient.”

Bucks T-4 Housing

Bucks T-4 Housing

Cutting Labor Costs, Shortening Schedules

IDCUBED’s first completed North American project, Bucks T-4 Housing in Blue Sky, Montana, is demonstrating how mass timber can be a fast, precise, and affordable way to build better, more attractive, more dignified workforce housing.

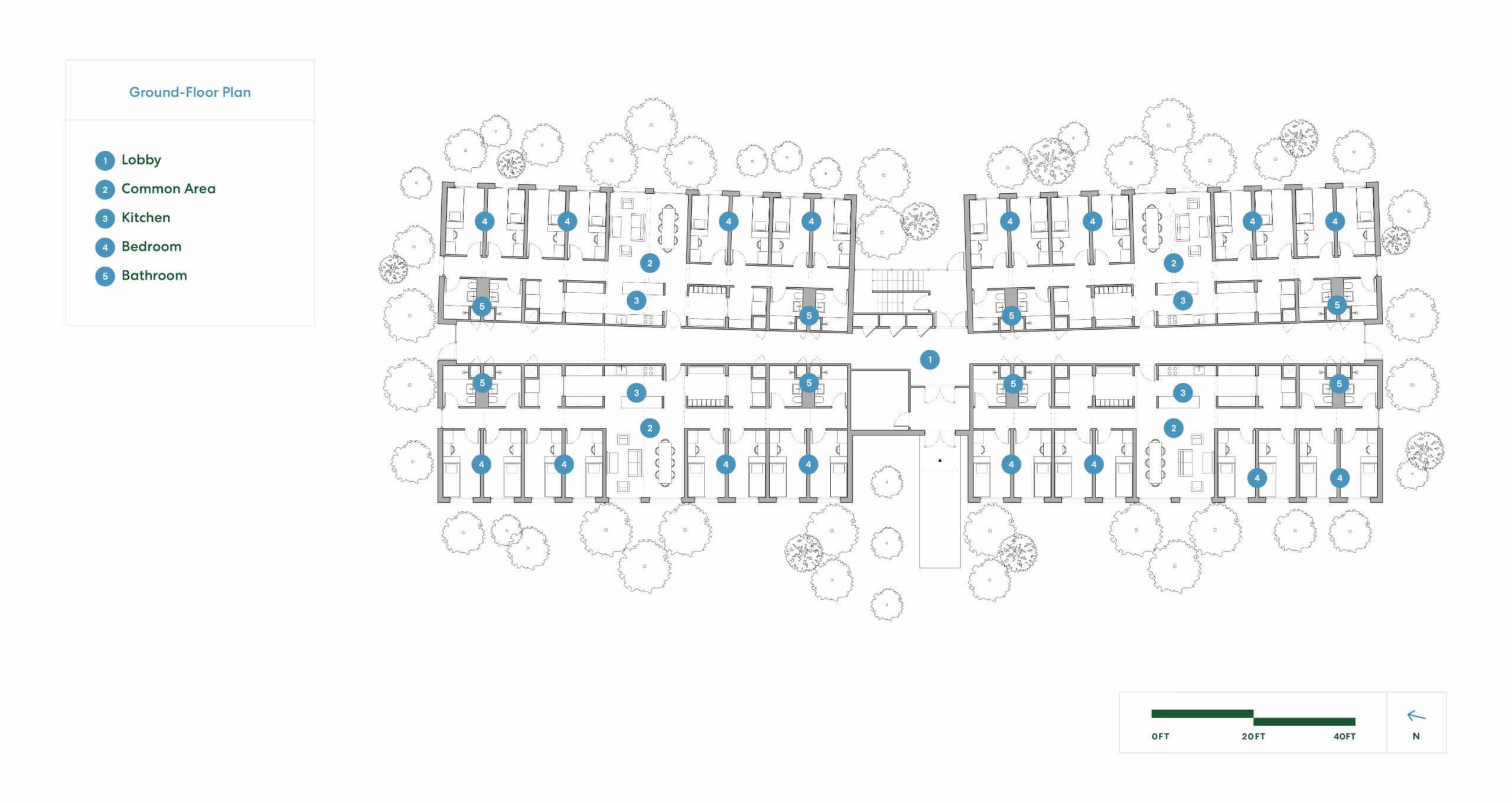

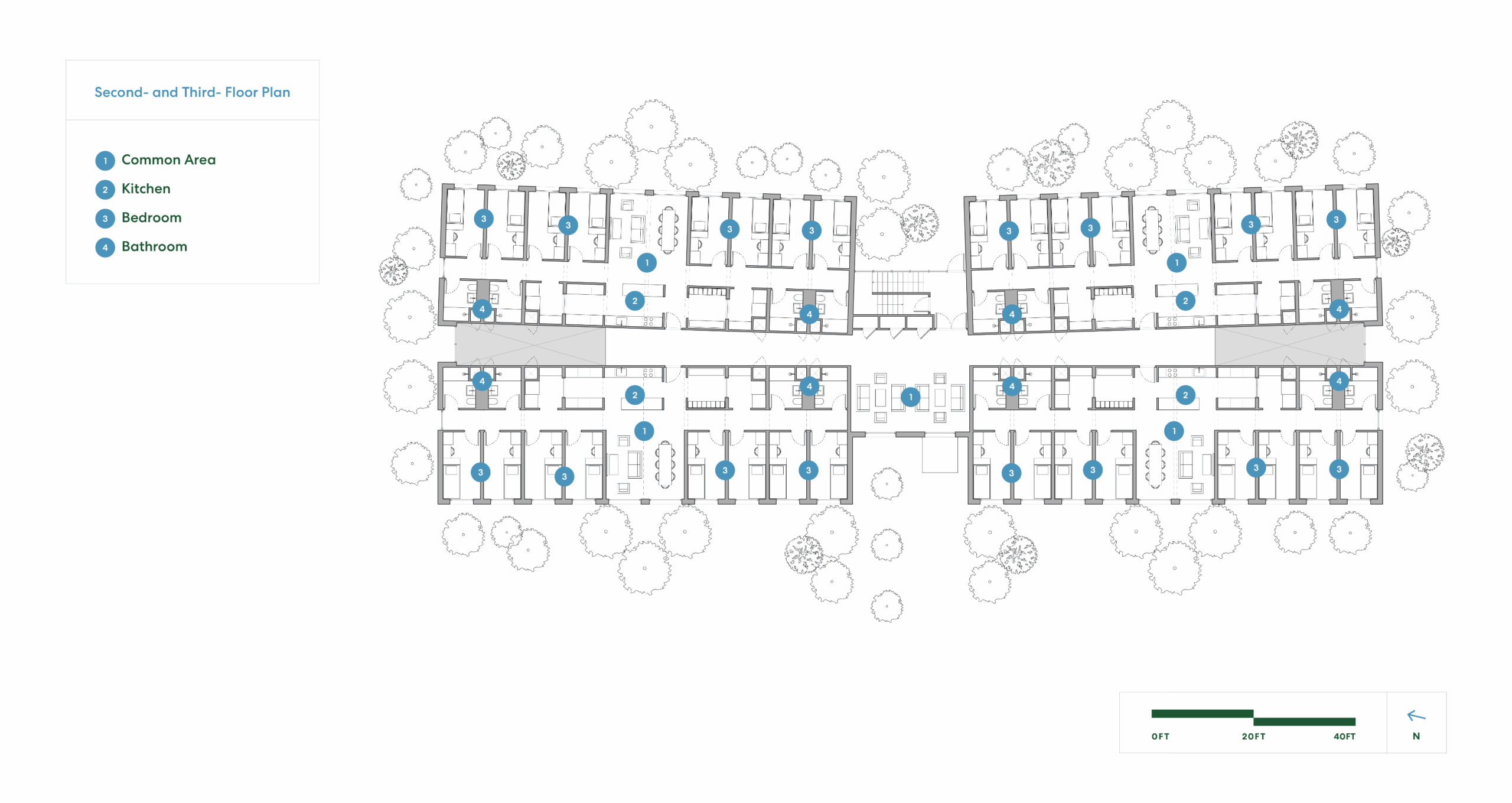

“Most workforce housing is boxes on parking lots,” Rose says. “We wanted this to feel like home—light, privacy, a sense of care.” The project is one of the first large-scale modular mass timber buildings in the United States—a 30,000-square-foot, three-story complex completed under budget in 11 months that can house just under 100 workers. Off-site fabrication of fully finished CLT modules cut labor costs, shortened schedules, and lowered overall expenditures by streamlining on-site assembly. By using mass timber in a modular system, the number of building parts drops by about 80 percent compared to conventional modular construction. And by creating a digital twin of the project, the IDCUBED team was able to coordinate building systems in advance, minimizing unknowns and reducing risk.

The project represents a critical milestone in IDCUBED’s North American operations, combining European modular expertise with a design tailored to the specific cultural and geographic context. In a region where worker accommodations are often temporary, cramped, and lackluster, the design team set out to create something fundamentally different—dignified housing that feels livable, welcoming, and well-crafted. The facility consists of private bedrooms, each in a shared apartment-style unit that includes shared kitchens, living areas, and bathrooms arranged for privacy and comfort.

Bucks T-4 Housing

Its design avoids the telltale signs of modular construction—visible seams, boxy repetition, and synthetic finishes—through precise CNC-fabricated CLT panels, strategic use of light and views, and thoughtful proportions. Interior walls, ceilings, and floors feature exposed Douglas fir CLT, offering both a warm visual texture and superior thermal and acoustic performance compared with conventional light-gauge steel modular housing.

Modules were shipped fully fitted, including plumbing, electrical, acoustic finishes, and windows, requiring only utility hookups and minor finishes onsite. While the original intent was to install cladding panels in the factory, the final decision was to apply Douglas fir siding onsite, simplifying logistics and improving finish quality. All other enclosure elements—insulation, weather barriers, and furring—were applied in the factory.

“There are two basic types of modules. One is a six-sided CLT box. The other is a five-sided CLT box with a glulam beam that holds up the edge,” Rose says. This hybrid system allows for larger, column-free spaces inside the modular units.

Modules were installed at a rate of up to 20 per day, with local crews—many unfamiliar with modular construction—quickly adapting to the straightforward assembly process. The development includes 120 mass timber modules, which collectively provide 96 workforce housing units.

“It’s a bit like the best stuff you get from IKEA,” Rose says. “If it’s well-done, it comes with the tools, the parts, no extras, and if you follow the directions, it goes together remarkably simply. And that’s what this is. The only tool really is a crane and a screw gun.”

In a location like Big Sky, where labor is scarce and workers commute long distances through dangerous mountain roads, these efficiencies were not just beneficial—they were essential.

“The labor was about one-third fewer people on-site for half the duration compared to traditional projects,” Rose says. “That’s less than half of the usual labor.” Though construction on this first project finished in 11 months, Rose believes that as they streamline processes, the team could complete future projects of this size in about 8 months.

“The subs were initially skeptical. They’d had bad experiences with modularity before. But after this job, they said, ‘We’d work like this again in a heartbeat,’” Rose says.

Bucks T-4 Housing

Bucks T-4 Housing

Agility and Scalability Key to a Sustainable Model

Unlike typical modular factories, which require assembly lines and other expensive equipment, mass timber modular assembly is nimble and cost-effective, making it easy to scale, Rose says. For the Bucks T-4 Housing in Big Sky, IDCUBED designed the modular system while its partner, Kalesnikoff, fabricated the CLT panels and assembled the modules at its facility. The completed units—fully fitted with finishes, cabinetry, and building systems—were then shipped to Montana for rapid on-site installation. “The sophistication is in the design, not the facility,” Rose says.

Rose and his team’s vision for IDCUBED is to ramp up to larger, multi-project endeavors. “Housing shouldn’t be built one building at a time,” Rose says. He envisions IDCUBED setting up assembly halls, where modules are put together, close to building sites to reduce shipping costs, fuel, and emissions while giving jobs to locals and sourcing materials as locally as possible.

The vision would also show that modular mass timber solutions can make beautiful spaces. “That seam—nearly imperceptible—told me we weren’t building boxes anymore. We were building something solid, seamless, and maybe even a little bit extraordinary.”

Bucks T-4 Housing

Project Details

- Project Name:

- Big Sky Bucks T-4 Modular Housing

- Location:

- Big Sky, Montana

- Architect:

- Owner:

- General Contractor:

- Modular Mass Timber Design & Project Delivery:

- Mass Timber Supplier & Module Assembly:

- Size:

- 30,000 square feet

- Timber Products: